On 15 December 2020, the Commission formally launched a legislative procedure by presenting a proposal for a regulation on fair and contestable markets in the digital sector, already known by the acronym DMA (‘Digital Market Act’). The most innovative elements of the DMA are twofold: the introduction of the legal figure of the gatekeeper and the elaboration of specific competitive obligations imposed on the latter. While the purpose and content of the notion of gatekeeper are relatively clear, the same cannot be said of the obligations imposed on them. In fact, Articles 5 and 6 contain a total of eighteen extremely heterogeneous and dissimilar types of requirements. This obscures the meaning and the competitive value of the DMA. The aim of the contribution is to unravel the skein of these obligations and to bring them as far as possible into the general categories of antitrust law. The analysis leads to the conclusion that a large part of the obligations provided for in the draft regulation is aimed at prohibiting practices which already fall within the scope of the antitrust rules, as demonstrated by the fact that such obligations have often been modelled on the cases investigated by the Commission under Articles 101 and 102. This does not detract from the fact that the systematic declension of antitrust principles in the digital sector carried out by the DMA has produced innovative provisions in their specificity. The detailed articulation of the competition obligations, the specification that in certain cases the intervention of public institutions is necessary to identify competitive conduct and the identification of the figure of the gatekeeper on the basis of sufficiently certain qualitative and quantitative parameters shift the center of gravity of the application of the principles of competition from ex post to ex ante, that is, from competition to regulation. This seems to be the qualifying and crucial element of the DMA proposal.

Il 15 dicembre 2020, la Commissione ha formalmente avviato una procedura legislativa presentando una proposta di regolamento sui mercati equi e contendibili nel settore digitale, già nota con l’acronimo DMA (“Digital Market Act”). Gli elementi più innovativi del DMA sono due: l’introduzione della figura del gatekeeper e l’elaborazione di specifici obblighi concorrenziali a carico di quest’ultimo. Mentre lo scopo e il contenuto della nozione di gatekeeper sono relativamente chiari, lo stesso non può dirsi in relazione agli obblighi imposti ad essi. Infatti, gli articoli 5 e 6 contengono un totale di diciotto tipi di obblighi estremamente eterogenei e dissimili tra loro. Ciò oscura il significato e il valore concorrenziale della DMA. L’obiettivo dell’articolo è quello di dipanare la matassa di questi obblighi e di ricondurli il più possibile nelle categorie generali del diritto antitrust. L’analisi porta alla conclusione che gran parte degli obblighi previsti dal progetto di regolamento mira a vietare pratiche che già rientrano nel campo di applicazione delle norme antitrust, come dimostrato dal fatto che tali obblighi sono stati spesso modellati sui casi indagati dalla Commissione ai sensi degli articoli 101 e 102. Ciò non toglie che la declinazione sistematica dei principi antitrust nel settore digitale operata dalla DMA abbia prodotto disposizioni innovative nella loro specificità. La dettagliata articolazione degli obblighi concorrenziali, la specificazione che in alcuni casi è necessario l’intervento delle istituzioni pubbliche per individuare le condotte concorrenziali e l’individuazione della figura del gatekeeper sulla base di parametri qualitativi e quantitativi sufficientemente certi spostano il baricentro dell’applicazione dei principi della concorrenza da ex post a ex ante, cioè dalla concorrenza alla regolazione. Questo sembra essere l’elemento qualificante e cruciale della proposta DMA.

Keywords: digital – Digital Markets Act – antitrust

CONTENUTI CORRELATI: digitale - Digital Markets Act - antitrust

1. Introduction. - 2. The specific features of large digital platforms and risks to competition. - 3. The gatekeeper and its obligations. - 4. Self-executing obligations under Article 5 of the DMA. - 5. The obligations under Article 6: prohibitions of discrimination. - 6. Other obligations under Article 6: prohibition of bundling, data portability, and equal access to data. - 7. Conclusions. - NOTE

In the last years the European Union has been trying to ensure the competitiveness of digital markets dominated by the so-called GAFAM (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple and Microsoft). Until now it has done so by resorting to the traditional instruments represented by Articles 101 and 102 TFEU. To limit only to the initiatives taken in 2020, it can be recalled that on 16 June the Commission opened an investigation against Apple regarding the terms of use of some of its apps [1]; on 10 November it sent a statement of objections to Amazon in relation to its business conduct in its dual capacity as marketplace and distributor [2]; on 17 December, the Commission authorized, but only under conditions, the acquisition of Fitbit by Google [3], against which it had already adopted three sanctions decisions between 2017 and 2019, imposing fines totalling EUR 8.25 billion [4].

However, the use of Articles 101 and 102 risks leading to unsatisfactory results for at least two reasons. First, in light of some peculiar features of digital markets, classical antitrust law requires some conceptual adjustments. To take the most obvious example, consider the circumstance that digital services are often offered to end users without monetary price, but in exchange – usually unknowingly – for data and information: in this way the age-old parameter used to determine the balance between supply and demand has disappeared. Secondly, antitrust law – which is characterized by synthetic and general prohibitions and a possible ex-post sanctioning measure – unveils a slow and uncertain capacity to intervene, given the systematic and wide-ranging nature of GAFAM’s business practices, as well as the speed with which they evolve and change. This is not about Achilles failing to catch up with the tortoise, but about a tortoise competing with Achilles.

On 15 December 2020, in an attempt to address these (and other) shortcomings, the Commission formally launched a legislative procedure [5] by presenting a proposal for a regulation on fair and contestable markets in the digital sector, already known by the acronym DMA (‘Digital Market Act’) [6]. On a subjective level, the DMA is directed towards large platform service providers named ‘gatekeepers’ (Art. 3). It then includes two provisions (Articles 5 and 6) which identify a wide range of obligations aimed at avoiding practices ‘unfair or limiting the contestability of the market’. Moreover, these obligations may be suspended (Art. 8), exempted on public interest grounds (Art. 9), or updated (Art. 10). Finally, from the procedural and sanctioning point of view, the DMA reflects the outline of Regulation No 1/2003 on the application of Articles 101 and 102. Like that regulation, it provides for broad powers of investigation and acceptance of commitments by the Commission (Articles 18-25) and for the imposition of fines, the amount of which may reach 10% of the gatekeeper’s total turnover (Article 26).

The most innovative elements of the DMA are twofold: the introduction of the legal figure of the gatekeeper and the elaboration of specific competitive obligations for the latter. While the purpose and content of the notion of gatekeeper are relatively clear, the same cannot be said of the obligations imposed on them. In fact, Articles 5 and 6 contain a total of eighteen extremely heterogeneous and dissimilar types of requirements. This obscures the meaning and the competitive value of the DMA. The aim of this contribution is therefore to try to unravel the skein of these obligations and to bring them as far as possible into the general categories of antitrust law. This should allow an assessment of the scope of the Commission’s legislative proposal, including its actual novelty and necessity. The article is organized as follows: in section 2, the specific features of digital platforms and the risks they present for the competitive dynamics of the market are analyzed. Section 3 examines the new notion of gatekeeper which, in the specific context of digital markets, stands alongside and to some extent overlaps with the notion of undertaking in a dominant position. Section 4 analyses and classifies the self-executing obligations contemplated by Article 5 of the DMA. While the obligations susceptible to further specification provided for in Article 6 are the subject of analysis and possible cataloguing in sections 5 and 6. Finally, the conclusions of the work are presented in Section 7.

Large digital platforms, a category to which GAFAM belongs, are characterized by three specific features [7].

First of all, from the point of view of business structure, they have very significant fixed costs – think for instance of search engine or operating system development costs or those related to IT R&D activities – but their marginal and variable costs that are instead close to zero, since the increase in the offer of a particular service does not entail any real increase in production costs: for instance, apps, once designed, can be replicated and downloaded indefinitely at virtually no cost. Moreover, large digital platforms often benefit from economies of scale and economies of scope. The latter, in particular, are important, since with the same IT and production equipment platforms are able to operate in many different markets: producing a search service for purchases does not have significant additional costs compared to a general search service.

Second, services provided through digital platforms are characterized by a very significant network effect, i.e. the number of users that use a service fosters, in itself, the increase of those users: for instance, if Amazon is the marketplace with the largest number of selling firms, this alone implies that more and more consumers will be induced to use Amazon for their on-line purchases and this, in turn, will induce other firms to join Amazon’s marketplace with the result of attracting an even higher number of potential buyers, and so on. This network effect is due to the fact that digital platforms usually operate in a multi-sided market, i.e. with at least two different categories of users who are, at the same time, the users of a service offered on one side and, so to speak, the ‘product’ sold to the users on the other side. In the example above, on one side of the marketplace, consumers can carry out their online shopping searches, and on the other side these searches are ‘sold’ to companies who use them to offer their products to consumers in a targeted manner. Correspondingly, companies are present in the marketplace because they can intercept a very high number of potential buyers and it is their presence that attracts them. It is also worth noting that the network effect does not necessarily occur due to the interaction between two or more sides of the marketplace, nor does it necessarily require that all categories of users operate on the platform with a business intent. For example, Facebook users use the platform primarily to maintain and develop their social contacts and it is the number of connections on the social side that creates the network effect; however, the network effect also reverberates on the business side of the platform: the more information obtained from the former, the higher the interest of business users to be present on the latter.

Finally, the third specific feature of digital platforms is represented by the crucial role of data, which constitute the fundamental assets of such firms, as they are the quantitative and qualitative ‘nourishment’ of their operating software. The higher the number and variety of data, the faster and more precise the algorithms process and produce services for users. To return to the examples given above, it is from the online searches carried out by users on one side of the marketplace that Amazon is able to obtain the data it sells to companies on the other side. And it is from the information that users channel to the social side of Facebook that the latter is able to identify possible buyers for the benefit of the business [8] side.

The above-mentioned salient features of digital platforms are likely to make their activities particularly sensitive from an antitrust point of view. In a competitive sense, large digital platforms often appear to be able to rapidly expand their activities in different markets, offering services and goods in an efficient and innovative manner. In an anti-competitive sense, however, once established as incumbents, such digital platforms, on the one hand, may impose onerous or discriminatory terms of use on their end-users and/or business users for whom they represent indispensable gateways between different sides of the market, and on the other hand, benefit from important protective barriers that make their position difficult to be contended even by equally or more efficient firms.

The particular competitive strength of digital platforms derives mainly from economies of scope. As mentioned, these allow different goods or services to be produced using the same production factors (specifically, first and foremost, the data and the algorithmic equipment to process them), that results in considerable cost savings compared to competitors that are not as digitized. The case of Amazon is exemplary in this respect. This platform started its business activity by intermediating online in the sale of books. Using the technological and logistical tools used for this market, it quickly extended its activities to the sale and distribution of a very wide range of products. In turn, the sale of huge volumes of goods enabled it to enter the market for the transport and delivery. By linking its fast delivery service, Amazon Prime, to a streaming service, Amazon subsequently entered the on-line film and TV series market, and from the latter it also entered the on-line music market (through Amazon Prime Music). As mentioned above, this expansive ‘soul’ of digital platforms, although it may raise concerns about the risks of foreclosing (less efficient) competitors, constitutes a strongly positive element from an antitrust perspective as it is often expressed in the offer of innovative and less costly services than those provided in a traditional manner.

As for the competitive risks posed by digital platforms, first of all, these platforms, as gateways between different sides of the market, benefit from a strong imbalance in terms of rights and obligations vis-à-vis their end and business users [9], allowing them to engage in abusive conduct, such as imposing onerous and/or discriminatory terms of use. Secondly, the competitive risks posed by digital platforms are represented by the difficult contestability of their position once they have established themselves as incumbents in the market, even by competitors that are able to offer goods or services of equal or even greater value. There are two main reasons for this reduced contestability. First, the network effect, which represents a daunting barrier to entry for potential competitors. To this regard it must be considered that since a service becomes more attractive on one side of the market the more users go on the other side, therefore a rival platform company has not only to offer a better quality and/or cheaper service, but also to convince a very high number of users to switch en masse from the service of the incumbent platform to its own (incumbency advantage). If (or as long as) such a migration does not take place, its service will still be less attractive to consumers [10]. This point is crucial in the context of an antitrust assessment. Where there is a network effect, on the one hand, it cannot be assumed that if a service is not chosen by users it is because of its lack of appeal, and on the other hand it does not necessarily appear to be true that the size of a firm derives from its efficiency, since it may well be the case that that firm is dominant simply because it entered the market first. The second reason why the position of an incumbent platform is difficult to contend with is the difficulty for competitors to access users data, data which, as noted, represent the crucial asset for the provision of digital services. Again, the network effect and economies of scope play in favor of the incumbent platform in data collection. The former, by causing an exponential increase in the number of users, necessarily induces a qualitative and quantitative increase in the flow of data; the latter because the increase in the number and variety of services offered by the platform necessarily increases the sources and types of data that can be collected. By contrast, competitors, when trying to enter the market, normally have much less and poorer quality data at their disposal.

It was mentioned in the first Section that the DMA identifies, as the object of the obligations it provides for, a new figure, called gatekeeper (Art. 1). The reasons for the introduction of this figure, which flanks and partly overlaps with that of the undertaking in a dominant position, are obvious. For the reasons mentioned in the previous section, a small number of large digital service providers are endowed with considerable economic power. The application of the classic antitrust rules (in particular Article 102 TFEU), which in any case remains possible, risks not being fruitful for the protection of the competitiveness of the markets concerned. First of all, it is only possible and ex-post, and it is therefore unable to prevent the extension, even over a long period of time, of conduct harmful to the interests of consumers and competitors. Secondly, in the case of unilateral conduct, the application of antitrust rules implies, in succession, the definition of the relevant markets – an operation which in the digital world often presents even greater complexities than in the ‘brick and mortar’ world – as well as the establishment of a dominant position in the identified market – a position which, in the case of digital service providers, may not exist in traditional terms.

In an attempt to resolve these difficulties, the DMA identifies gatekeepers on the basis of completely different parameters from those used by Article 102 to establish dominance in a market: the first relates to the type of services offered by the platform (qualitative parameter), the second concerns the dimensional elements of the platform (quantitative parameter).

With regard to the services offered, Art. 2 of the DMA, provides that a gatekeeper is a provider of at least one ‘core platform service’, i.e. one of the following: (a) online intermediation services; (b) online search engines; (c) online social networking services; (d) video sharing platform services; (e) number-independent interpersonal communication services; (f) operating systems; (g) cloud computing services; (h) advertising services, including advertising networks, advertising exchanges and any other advertising intermediary services, provided by a provider of one of the basic platform services listed in (a) to (g).

As regards the size profile, Article 3 of the DMA establishes that a provider is designated as a gatekeeper if it meets three cumulative conditions: (1) it has a significant impact on the internal market; (2) it operates a core platform service which constitutes an important gateway for business users to reach end users; (3) it has an entrenched and durable position in its business or can be expected to acquire such a position in the near future. Certain presumptions as to the fulfilment of these three conditions are also defined. The first one is presumed to be met if the undertaking to which the core platform service provider belongs has an annual turnover in the EEA of EUR 6,5 billion or more in the last three financial years, or if the average market capitalisation or equivalent fair market value of the undertaking to which it belongs was at least EUR 65 billion in the last financial year, and if it provides a core platform service in at least three Member States. The second requirement is considered to be present if the provider provides a core platform service with more than 45 million monthly active end-users established or located in the Union and more than 10 000 annual active business users located in the Union in the last financial year. Finally, the consolidated and sustained holding of the position of access point, referred to in the third requirement, is considered to be present if the thresholds referred to in the previous requirement have been reached in each of the last three financial years.

It should also be stressed that the status of gatekeeper is not directly applicable, but requires a decision by the Commission. Such a decision may be taken following the notification of the relevant information by the provider who considers himself to fall within this definition (Article 3, para. 4), or ex officio, following an investigation of the market (Article 3, para. 6) [11]. In the latter case, the Commission may find that a provider of core platform services should be designated as a gatekeeper if it meets the three dimensional conditions, but does not fall under one or more of the above presumptions.

According to its Article 1, the objective of the DMA is to ensure that markets in the digital sector in which gatekeepers are present are ‘fair and contestable’ throughout the Union. Three options were compared to prevent conduct contrary to this objective. The first option provided for a pre-determined list of gatekeepers who would be subject to a list of directly applicable obligations. The second option provided for a partially flexible framework for designating and updating obligations, involving a dialogue with the Commission to specify the conduct required to implement them. Finally, the third consisted of a totally flexible framework both as regards the identification of the person concerned and the obligations applicable to him.

The solution adopted in the DMA was essentially the second one, since it provides for a double list of obligations imposed on the gatekeepers. The first, contained in Article 5, sets out the obligations deemed self-executing, in the sense that compliance with them does not require further specification; the second, set out in Article 6, includes certain obligations whose implementation may require specification, which is obtained through dialogue with the Commission. In this regard, Article 7(2) makes it clear that if the Commission finds that the measures the gatekeeper intends to implement do not ensure effective compliance with the relevant obligations under Article 6, it may specify by decision the measures to be implemented by the gatekeeper in question.

As anticipated in the first section, he subdivision of obligations in the regulation, although functional to the objective of identifying the cases in which the Commission may intervene in a regulatory manner, obscures the meaning and the actual competitive scope of the DMA. Indeed, Articles 5 and 6 contain a total of 18 types of ‘obligations’ which are extremely heterogeneous and very dissimilar as regards the nature and characteristics of the conduct imposed. It is certainly true that, as mentioned, Article 1 of the DMA and the very title of Chapter III – where Articles 5 and 6 are inserted – evoke the need to prevent practices that ‘are unfair or limit contestability’, but it is not clear what this means in practice, nor whether and within what limits these obligations can be traced to the general categories of antitrust law, in particular those specific to abusive practices, such as exclusionary and exploitative conduct.

Some limited guidance can be drawn from Article 10 of the DMA. This provision, in fact, by providing that the Commission may identify new obligations for conduct by gatekeepers which is unfair or restrictive of contestability of services ‘in a manner similar to the practices covered by the obligations set out in Articles 5 and 6’, states that a practice shall be considered unfair or restrictive of contestability in two cases: (i) if an imbalance has arisen in terms of rights and obligations for business users and the gatekeeper is deriving an advantage from them that is not proportionate to the service provided to them; or (ii) the contestability of markets is diminished as a result of such a practice adopted by a gatekeeper. From the first case it is clear that the practice by which the gatekeeper, relying on the imbalance of power, succeeds in excessively compressing the utility of business users is to be considered ‘unfair’. In this perspective, the unfair practice could be conceptually led back to the category of abuse of exploitation. The second case, on the other hand, is objectively less useful, since it merely states, in a somewhat circular way, that the practice that produces this effect diminishes the contestability of markets. Here all that can be said is that a limitation or weakening of market contestability is inherently an exclusionary practice.

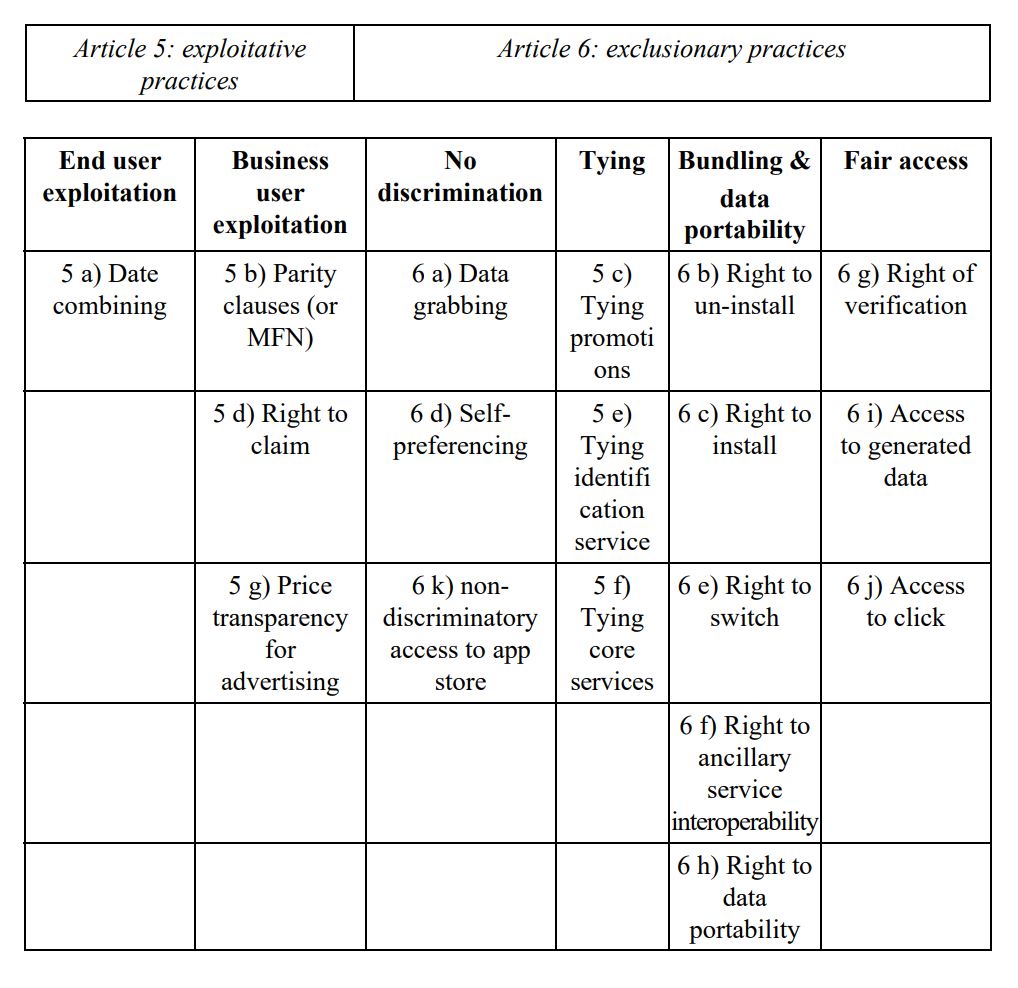

Trying to unravel the skein of the eighteen obligations contained in Articles 5 and 6, it can be noticed that in the first of these provision encompasses two general categories of obligations: both aimed at avoiding certain practices of exploitation of the end and business users of the services. In contrast, Article 6 includes four classes of obligations, all relating to exclusionary conduct, concerning discriminatory practices, tying, bundling (plus data portability) and, finally, obligation to ensure fair access to data.

This attempted classification is expressed in the table below, which will be explained in the following sections.

As mentioned, Article 5 contains two general categories of obligations: one concerning certain practices of exploitation of end-users and/or business users liable to be adopted by the gatekeeper and the other covering certain practices of the gatekeeper to exclude its competitors, which can be defined as tying.

The first category of obligations consists of the provisions contained in subparagraphs (a), (b), (d) and (g) of the provision, and can be qualified respectively as (i) ‘prohibition of unauthorized combination of data’, (ii) prohibition of parity clauses, (iii) right of appeal and (iv) right of transparency on the price of advertisements. The second category of obligations comprises the provisions contained in subparagraphs (c), (e) and (f) of Art. 5, and can be qualified collectively as (v) prohibitions of tying practices).

i) Prohibition of unauthorized combination of data (Art. 5(a))

The first obligation, consisting in the prohibition of unauthorized combination of data, is provided for in subparagraph (a) of the rule, which establishes that the gatekeeper must refrain from combining personal data obtained from the core platform services with personal data from any other service offered by the gatekeeper or with personal data from third party services, and must also avoid signing in end users to other services of the gatekeeper in order to combining personal data, unless the end user has been presented with the specific choice and provided consent pursuant to Regulation 2016/679.

The provision finds its inspiration in the Facebook case, which is still pending in Germany, but on which the German Federal Court of justice has already provisionally ruled.

According to the terms of exercise imposed on users, Facebook could combine, without asking for consent, data collected on the eponymous social service with data derived from other services it provides, such as Instagram and WhatsApp. The German Bundeskartellamt had banned such a combination, equating the breach of privacy regulations with an antitrust violation. The Federal Court upheld the ban, but changed its legal justification [12] . For the Court, the key issue is not the violation of privacy but the deprivation of any choice for end users between a highly personalized digital service through data combination, and a less personalized digital service based only on the data users share on a given social service. The lack of options available to Facebook users concerns both the profile of their personal autonomy and the exercise of their right to informational self-determination, which is also protected by the GDPR, and the profile relating to the competitiveness of markets. In this respect, the German Constitutional Court concluded that, according to the findings of the Bundeskartellamt, a considerable number of private Facebook users wanted to disclose less personal data, and if competition in the social network market had been effective, this option could have been expected to be available.

ii) Prohibition of parity clauses (Article 5(b))

Article 5, letter b) of the DMA contains the prohibition for the gatekeepers to use the so-called parity clauses or Most Favored Nation Clauses (MFN clauses), generally distinguished in ‘wide’ and ‘narrow’. Through the former, a platform that provides a service of price comparison requires its business users to offer their goods or services at the best price and at the best conditions of transaction practiced on any other sales channel [13]. By means of the latter, the comparison platform requires its business users to apply the same contractual conditions (or even better contractual conditions) offered on their own website.

Wide parity clauses have obvious anti-competitive effects that are not easily redeemable. Such clauses in fact: i) produce a chilling effect on the dynamics of prices: if a parity clause requires B to apply also to A the discount it intends to grant to C, it is possible that B, in order to avoid the duplication of the reduction in its revenues resulting from the double discount, decides not to grant the latter to either A or C [14]; ii) regardless of the above, they risk having a uniformising effect on prices and other transaction conditions: indeed, it is possible that competing platforms will also adopt such clauses in order to avoid that the tariffs they offer are higher than those charged elsewhere, with the consequent general effect of tariff equalization; iii) they may lead to an erosion of the profit margins of business users; indeed, if the platform increases the value of the commission it charges for the comparison service, business users cannot pass on this increase in their costs to the selling price of their goods or services, except by applying the increase to all distribution channels, with the inevitable important effect of reducing demand; (iv) they may constitute a barrier to entry, since possible competing platforms cannot attract business users by offering lower commissions. In contrast, narrow parity clauses, i.e. those imposing a level playing field only between the platform and the business user’s personal website, have much lower antitrust risk profiles. Indeed, on the one hand, there is a risk of price flattening only if business users do not consider offering their goods or services on their personal website on better terms than on the platform; on the other hand, such clauses can solve free rider [15] problems.

The provision contained in subparagraph (b) of Article 5 of the DMA prohibits the gatekeeper from imposing wide parity clauses, stipulating that the gatekeeper must allow business users to offer the same products or services to end users through third-party online intermediation services at prices or conditions different from those offered through the gatekeeper’s online intermediation services.

Moreover, the Commission has already prohibited the use of parity clauses by large digital platforms on the basis of antitrust rules. In 2012, the Commission opened an investigation against Apple and a number of international e-book publishers in relation to retail prices charged through MFN in iBookstore contracts. The case was resolved through commitments, including an obligation by Apple not to enter into or enforce any MFN retail pricing clauses in agreements with e-book retailers or publishers for five years [16]. In 2017, following an investigation opened against Amazon, the Commission concluded, once again in a decision accepting commitments, that a large range of parity clauses relating to different aspects of supply contracts (both price-related and related to other contractual terms) concluded by Amazon with e-book sellers should be considered as per se abusive under Article 102 [17].

iii) Right to claim (Article 5(d))

Article 5(d) states that gatekeepers shall refrain from preventing or restricting business users from raising issues with any competent public authority relating to any practices of gatekeepers.

Recital 39 of the DMA states that this prohibition is intended to safeguard a fair business environment and to protect the contestability of the digital sector. The public authority to which the provision refers is not clear. Since the exclusion of recourse to a judicial authority would be unlawful per se, it must be assumed that the provision refers to complaints to a non-judicial administrative authority. Recital 39 further specifies that business users might want, for instance, to complain about different types of unfair practices, such as discriminatory access conditions, unjustified closure of their accounts or unclear reasons for delisting products. The prohibition is, however, without prejudice to the right of business users and gatekeepers to set out in their agreements the conditions of use, including the use of legitimate complaint handling mechanisms and the use of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms or the jurisdiction of specific courts in accordance with relevant Union and national law.

iv) Transparency on prices of advertising services (Article 5(g))

Article 5(g) provides for a specific provision applicable to the prices of online advertising services that gatekeepers may provide to advertisers and publishers. Indeed, the provision stipulates that gatekeepers must provide advertisers and publishers to whom they provide advertising services, upon their request, with information concerning the price paid by them, as well as the amount or remuneration paid to the publisher, for the publishing of a given advertisement and for each of the relevant advertising services provided by the gatekeeper.

Recital 42 clarifies that it is motivated by the fact that the conditions under which gatekeepers provide online advertising services to business users often lack transparency. This market opacity is due to the extreme complexity of today’s programmatic advertising, which is likely to increase with the forthcoming removal of third-party cookies. The lack of information and knowledge for advertisers and publishers about the conditions of the advertising services they have purchased reduces their ability to switch to alternative online advertising service providers. Moreover, the costs of online advertising are likely to be higher than they would be in a more transparent platform environment, which is likely to be reflected in the prices end users pay for many everyday products and services that rely on the use of online advertising.

v) Prohibition of binding practices (Article 5(c), (e) and (f))

A wide range of obligations under the DMA refer to so-called binding practices. These, as is well known, include those business strategies whereby an undertaking makes the sale of one of its products or services (the main product or service) conditional upon the purchase of another product or service (the tied product or service) which is to be used or enjoyed together with the first product or service (e.g. a computer and a screen, or a car and its servicing) and is offered by the same or a related undertaking: thus, A sells its product (or service) X only if the buyer agrees to also purchase good (or service) Y produced by the same or related undertaking. Sometimes the binding practice is motivated by the desire to offer customers more efficient products, other times it is imposed by the technological interdependence between two products: for example, it may be that for technical reasons a certain software runs only or more efficiently on a certain hardware. In such cases, the practice is competitive in nature as it is likely to lead to an improvement in the price level and/or the quality of the product or service. The binding practice, however, may be used for anti-competitive purposes, for instance to foreclose competitors in the market for the tied good. If A is dominant in product market X, but not in product market Y – which however must be used together with X – A’s tying of its products in markets X and Y has an exclusionary effect on competitors in Y, irrespective of whether the latter’s goods are worse or better than A’s.

The Commission distinguishes binding practices into tying and bundling [18]. Tying’ refers to situations where customers who buy the tying product must also buy the tied product of the dominant undertaking. Bundling’, on the other hand, refers to the way the products are offered by the dominant undertaking and the way it sets its price. It is called ‘pure’ when the products are only sold together and in fixed proportions, or ‘mixed’ when the products are also available separately, but the sum of the individual selling prices is higher than the bundled price.

The binding practices applied by large digital companies have already been found incompatible with the antitrust rules of the Treaty on several occasions. In 2007, the EU General Court upheld the Commission’s decision that Microsoft’s making the supply of the Windows operating system conditional on the simultaneous purchase of Windows Media Player software was abusive [19]. In 2018 [20], the Commission ruled that Google’s imposition of an obligation on Android device manufacturers to pre-install Google search and Google Chrome apps as a condition for granting a licence to use the Play Store, i.e. Google’s app store, which users considered indispensable and expected to find installed on their device [21], was abusive.

Article 5 of the DMA contains several obligations aimed at preventing more or less obvious forms of tying. For example, 5 c) stipulates that the gatekeeper must allow business users to promote offers to end users acquired through the core platform service and to conclude contracts with these end users, regardless of whether they use the gatekeeper’s core platform services for this purpose or not; furthermore, the gatekeeper is obliged to allow end users to access and use content, subscriptions, components or other items through the gatekeeper’s core platform services using a business user’s software application, if the end users have purchased such items from the business user in question without using the gatekeeper’s core platform services. Furthermore, 5(e) provides that the gatekeeper must refrain from requiring business users to use or offer its identification service [22], or to interoperate with it, in the context of the services offered by business users using the gatekeeper’s core platform services. Finally, pursuant to 5(f), the gatekeeper must refrain from requiring business users or end users to subscribe to or register with any other core platform service identified pursuant to Article 3 or which meets the thresholds set out in Article 3(2)(b) as a condition for accessing, registering or subscribing to any of the gatekeeper’s core platform services identified pursuant to that Article.

As mentioned, the obligations of gatekeepers provided for by Article 6, i.e. may be subject to further specifications. Although they are all aimed at eliminating the risk of exclusionary conduct on the part of the gatekeeper, a first group can be brought under the general category of the prohibition of non-discrimination. These prohibitions can be qualified as follows: (i) prohibition of data grabbing (Article 6(a)); (ii) prohibition of self-preferencing (Article 6(d)); and (iii) prohibition of discriminatory conditions of access to the app store (Article 6(k)).

i) Prohibition of data grabbing (Artice 6(a))

In some circumstances, a gatekeeper may play the dual role as a provider of core platform services to business users, as well as a provider of services that compete with those offered by such business users. In these circumstances, a gatekeeper could use the data generated by the core services to gain an advantage in competing markets. In order to avoid such a distortion of competition, Article 6(a) provides that the gatekeeper must refrain from using, in competition with business users, non-publicly accessible data generated through the activities of those users of its core services or by the end users of those business users.

The provision is intended to cover several situations. For example, it is possible for a gatekeeper to provide a marketplace or app store to business users, while at the same time offering services as an online retailer or application software provider in competition with those same business users. It applies (a fortiori) also to the case where the data are not generated by the use of the underlying service, but provided to it by the business user. In the case of cloud computing services, the obligation should also extend to data provided or generated by the gatekeeper’s business users in the context of their use of the cloud computing service, or through the gatekeeper [23] ‘s app store.

The practice, which can be defined as ‘data grabbing’, already has a precedent under Article 102. In the Statement of Objections sent to Amazon in 2020 [24], the Commission states that the company plays a dual role: on the one hand, it represents a marketplace where third-party sellers can offer their products directly to consumers, and on the other hand, it itself offers products on its marketplace as a retailer, thus competing with third-party sellers. As a provider of marketplace services, Amazon has access to third-party sellers’ non-public business data, such as the number of units ordered and shipped of products, the sellers’ revenue on the marketplace, the number of visits to the sellers’ offerings, shipping data, past performance, and other consumer enquiries related to the products, including warranties. The Commission considered that large amounts of non-public data from third-party sellers flow into the hands of Amazon’s retail entities who are able to aggregate this data in an automated manner and use it to calibrate those offers and to make strategic business decisions. For example, the taking of competitors’ data would allow Amazon to focus its sales on the best-selling products in all product categories and to adjust its offers in the light of data from competing sellers. In the Commission’s view, the use of non-public data of third-party sellers allows Amazon to avoid the normal risks of retail competition and to exploit its dominant position in the market for the provision of marketplace services, thereby infringing Article 102.

ii) Prohibition of self-preferencing (Article 6(d))

Article 6(d) of the DMA obliges gatekeepers to refrain from treating more favourably in ranking services and products offered by the gatekeeper itself (or offered by third parties belonging to the same undertaking as the gatekeeper) compared to similar services or products of third parties and requires gatekeepers to apply fair and non-discriminatory conditions to such ranking.

The practice, which is already known as self-preferencing, clearly falls within the general class of prohibition of discrimination; however, it presents its own specific legal categorization because it assumes the ability of the platform to classify or order according to one or more criteria established by it the products or services of the companies operating through its services. It therefore does not cover all cases in which a person discriminates against a competitor’s product or service in relation to his own, but only cases in which this is done by means of a ranking [25].

There are numerous cases in which this practice has been censured by the Commission on the basis of Article 102.

The first is the 2017 decision [26], which found that Google had abused its dominant position by systematically giving a prominent position to its own comparison shopping service Google Shopping, in the sense that when a consumer performed a search for a product for which Google Shopping wanted to offer results, these were always displayed at the top of the search. Correlatively, Google downgraded the comparative shopping services of its competitors in the search results pages.

A similar self-preferencing practice was reproached to Google in the Commission’s 2019 [27] decision. According to the Commission, Google, through its AdSense for Search service, linked advertisements to users’ search results, i.e. it acted as an advertising intermediary between advertisers and publishers interested in profiting from advertising space linked to pages selected by users. According to the Commission, Google, by means of so-called ‘premium placement’ clauses, required publishers both to reserve the most profitable space for Google’s ads and to provide for a minimum number of ads collected by Google. As a result, Google’s competitors were prevented from placing their advertisements in the most visible and clicked-on spaces of the pages displayed on their websites.

Finally, self-preferencing can also be said to apply to the practice reproached to Amazon in the Statement of objections sent to it in 2020 [28]. Indeed, the Commission assumed that the criteria Amazon sets to select the winner of the so-called Buy Box and to allow sellers to offer products to Prime users lead to a preferential treatment of Amazon’s retail business or of sellers using its logistics and delivery services. The Buy Box is prominently displayed on the platform’s websites and allows customers to add items from a specific retailer directly into their shopping carts. For marketplace sellers, being chosen as the offer that appears in the Buy Box is crucial as it prominently displays a single seller’s offer for a chosen product on Amazon’s marketplaces, and generates the majority of all sales.

iii) Non-discriminatory access of competitors to the app store (Article 6(k))

Article 6(k) requires the gatekeeper to apply fair and non-discriminatory general terms and conditions of access for business users to its software application store (app stores), designated pursuant to Article 3 of the Regulation.

Recital 57 clarifies that general access conditions should be considered unfair if they result in an imbalance in the rights and obligations imposed on business users, or if they give the gatekeeper a disproportionate advantage in relation to the service it provides to them, or if they place business users at a disadvantage in providing identical or similar services to those provided by the gatekeeper. The same recital specifies that in order to assess the possible unfairness of the general conditions of access, the following may serve as a benchmark: (i) the prices charged or conditions imposed for identical or similar services by other app store providers; (ii) the prices charged or conditions imposed by the app store provider for other services, related or similar, or provided for the benefit of different types of end users; (iii) the prices charged or conditions imposed by the app store provider for the same service in different geographical regions; (iv) the prices charged or conditions imposed by the app store provider for the same service that the gatekeeper offers to itself. It follows, therefore, that Article 6(k) lays down conceptually similar rules for the service of access to the app store which have been developed by case law for cases of excessive prices (parameters (i), (ii) and (iii)) [29] and margin squeeze (parameter (iv)) [30].

This specific obligation also finds a reference in the framework of the application of Article 102. In fact, in 2020, the Commission opened an investigation against Apple, following a complaint by a competitor in the music streaming market (Spotify), on the grounds that this company would impose in its agreements with companies wishing to distribute applications to users of Apple devices (i) the compulsory use of the purchasing system belonging to Apple itself (in-app “IAP”) for the distribution of paid digital content, charging app developers a commission (of 30%) on all subscription fees made through IAP; (ii) restrictions on the ability of developers to inform users about alternative purchase options outside the apps [31] e.g. on the developer’s website where they can usually be found at a lower price.

Article 6 of the DMA contains other provisions that can be grouped according to their competitive nature. These are the provisions containing the prohibition of bundling, the right to data portability and finally those prohibiting unfair restrictions on access to data and information.

i) Prohibition of bundling (Article 6(b), (c), (e) and (f))

A first group of provisions in Article 6 contains obligations aimed at avoiding bundling practices, i.e., as mentioned above, sales organized in such a way that the services offered can only be used jointly, or even separately, but under more onerous conditions. In the provision under consideration, this is done by recognizing the rights of freedom of choice of both end users and business users. In fact, the norm requires the gatekeeper: i) to allow end users to uninstall any software application pre-installed on their core service (letter b [32]; ii) to allow the installation and effective use of software applications or software application stores of third parties that use the gatekeeper’s operating systems or that are interoperable with them, iii) to allow access to such software applications or software application stores by means other than the core platform services of such gatekeeper [33] (letter c); iv) to refrain from using any software applications or software application stores of third parties that use the gatekeeper’s operating systems or that are interoperable with them. (iv) refrain from technically restricting the ability of end users to switch to and subscribe to different software applications and services to which they have access using the gatekeeper’s operating system; this also applies to end users’ choice of internet access provider (letter e)).

In addition, Article 6(f) requires gatekeepers to allow business users and ancillary service providers access to and interoperability with the same operating systems and hardware and software systems that are available to or used by the gatekeeper for the provision of its ancillary services. It follows from recital 52 that the provision is intended to apply where gatekeepers have the dual role of operating system developers and device manufacturers. In such circumstances, a gatekeeper could limit access to some of the device’s functionalities (e.g. short-range communication and related software), which may be necessary for the provision of an ancillary service either by the gatekeeper or by a third-party provider. Such access limitation is likely to weaken the incentives for innovation by providers of ancillary services as well as the end-users’ choice of such services.

ii) Data portability (Article 6(h))

Large digital platforms benefit from access to huge amounts of data that they collect while providing both their own services and the services of third parties operating on those platforms. This is likely to favour these platforms over their competitors and reduce the contestability of their market position. One of the solutions that can be explored to keep competition alive is to provide that business and end users can transfer their data (and any data generated by them) to other competing digital service providers. Facilitating switching or multi-homing leads to more choice for business and end-users and an incentive for all operators to innovate. In this perspective, Article 6(h) of the DMA states that the gatekeeper must ensure the effective portability of data generated through the activity of a business user or end-user and must in particular provide tools to end-users to facilitate the exercise of data portability, in line with Regulation (EU) 2016/679, including through the provision of seamless, real-time access.

The reference to the so-called Privacy Regulation applies in particular to Article 20 thereof, which provides for the right to the portability of personal data. This implies that the data subject has the right to receive from the gatekeeper the data generated by it and to transmit it to a third party in a structured, commonly used and machine-readable format. However, it should be underlined that, under the Privacy Regulation, the right of portability does not entail the obligation of effective interoperability, since Recital 68 of that Regulation clarifies that the portability of personal data covered by Article 20 does not imply an obligation for data controllers to adopt or maintain technically compatible processing systems.

iii) Unfair restrictions on access to data and information (Article 6(g), (i) and (j))

The issue of access to data held by a digital platform by its business and/or end users is undoubtedly one of the most complex and controversial. In principle, mandatory sharing of a company’s assets not only infringes the right to property, but also risks significantly diminishing incentives to invest and innovate, as the results of such investments may have to be shared with competitors. For these reasons, the European Courts have accepted that a refusal to supply a good or service, even if opposed by a dominant undertaking, may constitute an abuse only under the very restrictive conditions defined in the so-called essential facilities [34] doctrine.

The application of this doctrine to digital platforms in relation to the data they possess, aimed at enabling other firms to produce competing or complementary goods or services, presents additional difficulties to those – already not insignificant – encountered in the case of tangible assets (e.g., infrastructures) or intangible assets (IP) in relation to which it was developed. Unlike these goods, the data constitute a heterogeneous asset susceptible to differentiated uses: for example, the string of Internet searches carried out by a user can be used to infer his interests in the real estate market, as in that of tourist services. Finally, access by third parties to data collected by a company almost inevitably crosses the privacy protection rules applicable to personal data, in compliance not only with Regulation 2016/679, but also with the Charter of Fundamental Rights.

The DMA does not provide for a generalized right of access to data, but it does provide for three specific obligations.

The first is set out in Article 6(g) and provides that the gatekeeper must provide advertisers and publishers, at their request and free of charge, with access to its performance measuring tools and information necessary for them to carry out an independent verification of the supply of ad inventory. This obligation is designed to counteract the fact that the conditions under which gatekeepers provide online advertising services to business users are often opaque and non-transparent, resulting in limited information being available to advertisers and publishers on the effect of a given ad.

The second obligation concerns data generated by the users themselves, both business and end users. This is a vast amount of information that is valuable from an economic point of view. In order to ensure that business users have access to the relevant data thus generated, Article 6(i) provides for an obligation on the gatekeeper to provide business users, or third parties authorised by them, with effective access to aggregated and non-aggregated data free of charge, and to ensure under the same conditions the use of data which are provided or generated in the context of the use of the core platform services by such business users as well as by end users who make use of products or services provided by such business users. With regard to personal data, the gatekeeper shall only provide access to those data directly related to the use made by the end user in connection with the products or services offered by the business user through the basic platform service and where the end user accepts such sharing by expressing consent pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2016/679.

Finally, Article 6(j) provides for a specific data access obligation in favour of third-party providers of search engines. This is by far the most significant obligation from a competition point of view. As mentioned in recital 56, the value of online search engines increases as the total number of business and end users increases. Online search engine providers collect and store aggregated data sets containing information about users’ searches and how users have interacted with the results of those searches. Online search engine service providers collect this data both from searches made through their own online search engine and from searches made on their business partners’ platforms. Access by gatekeepers to such ranking, query, click and display data constitutes an important barrier to entry, which hinders the contestability of online search engine services. Subparagraph (j) provides that the gatekeeper must provide any third-party provider of online search engines, upon their request, with access on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory terms to ranking, query, click and display data in relation to free and paid search generated by end-users on the gatekeeper’s online search engines, subject to anonymisation for query, click and display data that constitute personal data.

As mentioned above, when analysed from the perspective of its effectiveness on the competitiveness of digital markets, the DMA can be confusing. Since it is still a proposal for a regulation, some modifications seem to be advisable.

The circumstance that some obligations imposed on gatekeepers are self-executing and others may require a dialogue with the Commission for their compliance does not justify the division made. It would be possible, for example, to classify the obligations according to the type of practices they are intended to regulate and to identify in an ad hoc rule which of these obligations are susceptible to specification by the Commission. This would make it possible to correct certain debatable classificatory solutions. For example, many of the obligations contained in both Article 5 and Article 6 concern the prohibition of tying practices (Article 5(c), (e) and (f); Article 6(b), (c), (e) and (f)), which share the same anti-competitive nature, even though they may take the form of tying or bundling. One might therefore consider placing them in the same rule, probably through more comprehensive and simplified provisions. The same could be said for the obligations relating to discriminatory practices (Article 6(a), (d), (k)): there does not seem to be a substantial distinction between the grabbing of competitors’ data in order to favour one’s own services (sub-paragraph (a)), the preferential positioning of one’s own services in the results pages of a search (sub-paragraph (d)), or the imposition of discriminatory conditions for competitors’ access to the app store (sub-paragraph (k)).

The above analysis also leads to the conclusion that the Commission has employed a conceptually conventional approach in the DMA. As we have seen, a large part of the obligations provided for in the draft regulation is aimed at prohibiting practices which already fall within the scope of the antitrust rules, as, moreover, demonstrated by the fact that such obligations have often been modelled on the cases investigated or being investigated by the Commission under Articles 101 and 102. This does not detract from the fact that the systematic declension of antitrust principles in the digital sector carried out by the DMA has produced innovative provisions in their specificity. I refer, for instance, to the obligation imposed on gatekeepers to refrain from combining personal data obtained from different services of the gatekeeper itself and/or of third parties (Article 5(a)), which translates in detailed terms the principle of freedom of choice of consumers sometimes evoked, but often only in generic terms, in European case law. Also worthy of note is the right to data portability (Article 6(h)), which, although clearly of a competitive nature, had no precedent in terms of application on the basis of Articles 101 and 102, and has instead been transferred from the privacy rules. Finally, of great importance appears to be the obligations laid down to guarantee access to the data by competitors of the gatekeepers (Article 6(g), (i), (j)), access which would hardly be possible on the basis of the doctrine of essential facilities alone.

In any case, the detailed articulation of the competition obligations, the specification that in certain cases the intervention of public institutions (the Commission) is necessary to identify competitive conduct and the identification of the figure of the gatekeeper on the basis of sufficiently certain qualitative and quantitative parameters shift the center of gravity of the application of the principles of competition from ex post to ex ante, that is, from competition to regulation. This seems to be the qualifying and crucial element of the DMA proposal.

[1] Antitrust: Commission opens investigations into Apple's App Store rules (Press release).

[2] Antitrust: Commission sends Statement of Objections to Amazon for the use of non-public independent seller data and opens second investigation into its e-commerce business practices (Press release).

[3] Mergers: Commission clears acquisition of Fitbit by Google, subject to conditions (Press release).

[4] 27 June 2017, Antitrust: Commission fines Google € 2.42 billion for abusing dominance as search engine by giving illegal advantage to own comparison shopping service (Press release) (the decision is being appealed before the General Court in case T-612/17; 18 July 2018, Antitrust: Commission fines Google €4.34 billion for illegal practices regarding Android mobile devices to strengthen dominance of Google’s search engine (Press release); 20 March 2019, Antitrust: Commission fines Google €1.49 billion for abusive practices in online advertising (Press release). Moreover, in 2020, EU action was complemented by action by some Member States, primarily Germany and Italy. On 23 June, the German Supreme Court (Bundesgerischtshof) essentially endorsed the Bundeskartellamt’s view that Facebook’s terms of use of user data constituted an abuse of a dominant position. On 20 October, the Italian Competition Authority opened an investigation against Google for exclusionary abuses.

[5] The literature on the application of antitrust rules to digital platforms is now very extensive. We will therefore limit ourselves to listing those contributions to which we have most usefully referred: P. AKMAN, Competition Law Assessment of Platform Most-Favored-Customer Clauses, 2016, J. of Comp. L. & Econ., 781 ss.; A. EZRACHI, M. STUKE, Virtual competition, Cambridge Mass. & London Eng., 2016, 346; M.E. STUKE, A.P. GRUNES, Big Data and Competition Policy, Oxford, 2016, 338; A. CANEPA, I mercati dell'era digitale – Un contributo allo studio delle piattaforme, Turin, 2020, 151; G. COLANGELO, M. MAGGIOLINO, Big data, data protection and antitrust in the wake of the bunderskartellamt case against Facebook, in Italian Antitrust Rev., 2017, 104 ss.; M.R. PATTERSON, Antitrust law in the new economy, Cambridge Mass. & London Eng., 2017, 310; L. KHAN, Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox, 2017, Vol. 126, 710 ss.; B. KLEIN, The Apple e-books case: When is a Vertical Contract a Hub in a Hub-and-Spoke Conspiracy?, in J. of Comp. L. & Econ., 2017, 423 ss.; P. MANZINI, Prime riflessioni sulla decisione Google Android, Eurojus, 2018.; P. MANZINI, Le restrizioni verticali della concorrenza al tempo di internet, in Dir. comm. int., 2018, 289 ss.; M. KATZ, J. SALLET, Multisided Platforms and Antitrust Enforcement, 2018, The Yale L. J., Vol. 127, 2142 ss.; L. KHAN, The Separation Of Platforms and Commerce, in Columbia L. Rev., 2019, Vol. 119, 973 ss.; N. PETIT, Are ‘Fangs’ Monopolies? A Theory Of Competition Under Uncertainty, 2019, Working paper; M. INGLESE, Regulating the Collaborative Economy in the European Union Digital Single Market, 2019, 171; W.P.J. WILS, The obligation for the competition authorities of the EU Member States to apply EU antitrust law and the Facebook decision of the Bundeskartellamt, Concurrences N° 3-2019 l 58 pp.; P. IBÁÑEZ COLOMO, Self-Preferencing: Yet Another Epithet in Need of Limiting Principles, World Competition, 2020, 417 ss.; D.A. CRANE, Ecosystem Competition, OECD Note, 2020, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/

COMP/WD(2020)67/en/pdf; A. DE STREEL, Should digital antitrust be ordoliberal?, Concurrences N° 1-2020 I, 1 ss.; A. FLETCHER, Digital competition policy: Are ecosystems different?, 2020, OECD Note, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/WD(2020)96/en/pdf; M. BALL, Apple, Its Control Over the iPhone, The Internet, And The Metaverse, 2021, https://www.

matthewball.vc/all/applemetaverse.

[6] European Commission, Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on fair and contestable markets in the digital domain (Digital Markets Act), 15 December 2020 COM(2020) 842 final. The proposal is accompanied by a second proposal for a regulation on the single market for digital services, called the Digital Services Act (DSA). In addition, in 2020, Regulation No 2019/1150 came into force to promote fairness and transparency for business users of intermediary services.

[7]See generally: J. CRÉMER, Y.-A. DE MONTJOYE, H. SCHWEITZER, Competition Policy for the Digital Era, Final Report, Luxembourg – Publications Office of the European Union, 2019; AGCM, AGCOM, Garante protezione dati personali, Indagine conoscitiva sui Big Data, Roma, 2019; J. FURMAN et al., Unlocking Digital Competition, Report of the Digital Competition Expert Panel, London, 2019; F. FUKUYAMA, B. RICHMAN, A. GOEL, R.R. KATZ, A. DOUGLAS MELAMED, M. SCHAAKE, Report of The Working Group On Platform Scale, Stanford University, 2020.

[8] A heuristic classification of data collection methodologies contemplates three cases: (a) data may be ‘communicated’ directly by users, such as in the case of comments on social networks, videos posted, ‘likes’ or similar, compilation of rankings related to preferences for films, TV series, songs, etc; b) data can be ‘observed’, i.e. obtained from the online activity of the users, for example, from the type of searches carried out on the internet, from the geographical movements of the individuals as witnessed by the positioning of the mobile phones, or from the sports and health information transmitted through IOT instrumentation; finally, c) certain data can be ‘inferred’ through a more sophisticated elaboration of those ‘communicated’ or ‘observed’: automated processing of the latter, for instance, can infer users’ spending capacity or preferences, or their political and/or religious orientation, or sexual orientation, and so on.

[9] It is all too obvious that, today, practically no company can operate effectively without the use of Google, Amazon, and/or Facebook, or without being reachable by means of IT equipment compatible with that of the Apple (IOS) and/or Google (Android) operating systems.

[10] J. CRÉMER ET AL., Competition Policy, (fn 7), describe this network effect as the classic egg/goose problem: to attract users on side A, a platform must attract users on side B, but to attract users on side B it must attract users on side A (p. 36). Seen from the angle of the challenging enterprise, however, it looks more like a version of Catch-22.

[11] As provided for in Articles 14-17 of the DMA.

[12] Federal Court of Justice provisionally confirms accusation of abuse of a dominant position by Facebook, 23 June 2020, No. 80/2020, https://www.bundesgerichtshof.de/SharedDocs/

Pressemitteilungen/DE/2020/2020080.html.

[13] For instance, A requests B to automatically benefit from the same terms of supply as the latter may stipulate with C, if they are more favourable than those of A.

[14] Obviously, the larger the economic size of the incumbent, the more significant is the chilling effect on price decreases; from the point of view of profit reduction, it is one thing to grant a discount to a company that absorbs, say, 5% of sales, quite another to grant it to a company that serves as an outlet for 50% of sales.

[15] For example, in the case of online booking platforms for hotel services, if hotels were free to charge a lower price on their personal website than the one indicated on the platform, they would benefit parasitically from the advertising and comparison services provided by the platform. The narrow price parity clause induces users to buy hotel services on the platform, which is thus able to obtain compensation for its services. A second type of positive effect of parity clauses is the possible resolution of the so-called hold-up risk. If the distributor could not be sure that its competitors would not benefit from lower purchase prices than its own, it would refrain from making the investments, because these would obviously be negative for its budget.

[16] European Commission, Decision of 12 December 2012, CASE COMP/AT.39847-E-BOOKS.

[17] European Commission, decision of 4 May 2017, case AT.40153 – MFN clauses for e-books and related issues, see summary in OJEU C 264/7, 11 agosto 2017.

[18] Communication from the Commission – Guidance on the Commission's enforcement priorities in applying Article 82 of the EC Treaty to abusive exclusionary conduct by dominant undertakings, OJEU C 45, 24 February 2009, 7-20, 47 et seq.

[19] Judgment of 17 September 2007, Microsoft and Others v. Commission, T201/04-, ECLI:EU:T:2007:289.

[20] Decision cited above, see footnote 1.

[21] Article 102 expressly prohibits tying practices in Article 102(d), which prohibits making the conclusion of contracts subject to the acceptance by the other parties of supplementary obligations which by their nature or according to business usage have no connection with the subject matter of the contracts. In Microsoft v. Commission, cited above, the Court developed a test for the legality of tying practices in line with Art. 102(d), see 842-869.

[22] Within the meaning of ar. 2, no. 14 of the DMA, an identification service means an auxiliary service which enables any kind of verification of end users or business users, irrespective of the technology used.

[23] Although it is an obligation aimed at avoiding the acquisition of an unlawful advantage through the misappropriation of data, in some ways it could be qualified as a unilateral variation of the exchange of information between competitors prohibited by Article 101, a variation that is possible because of the characteristics of digital platforms. Just as, according to well-established case law, competing companies cannot exchange commercially sensitive information but must independently determine the conduct they intend to follow on the market, the digital platform cannot appropriate commercially sensitive information of competitors in order to determine its conduct by taking it into account instead of independently addressing the risks of competition.

[24] Supra (fn 1).

[25] In order to ensure that this obligation is effective and cannot be circumvented, it should also apply to any measure which may have an equivalent effect to differential or preferential treatment in the ranking. The guidelines adopted pursuant to Article 5 of Regulation (EU) 2019/1150 should also facilitate the implementation and enforcement of this obligation.

[26] Supra (fn 1).

[27] Supra (fn 1).

[28] Supra (fn 1).

[29] As regards overpricing, case law has developed two tests which may be used alternatively. The first, the so-called UBC test, is to determine whether there is an excessive disproportion between the cost actually incurred and the price actually charged and, if so, whether an unfair price has been charged, both in absolute terms and in comparison with competing products (see judgment of 14 February 1978, United Brands and United Brands Continentaal v Commission, 27/76, EU:C:1978:22, paragraph 252). The second, the Tournier-Lucazeu test, is based instead on a comparison on a homogeneous basis of the price levels charged in different Member States and the possible establishment of an appreciable difference between them (see judgments of 13 July 1989, Tournier, 395/87, EU:C:1989:319, paragraph 38, and of 13 July 1989, Lucazeau and others, 110/88, 241/88 and 242/88, EU:C:1989:326, paragraph 25).

[30] With regard to the margin squeeze, i.e. the squeezing of competitors’ margins that an undertaking may carry out by owning a component that is essential to the production of a good or service, case law has established that it is abusive where the dominant undertaking charges a higher price for the component than that at which the complete good or service is sold to final consumers, or where the difference between the final price and the price of the component is not sufficient to cover the costs that the dominant undertaking itself incurs in providing the good or service (see Judgment of 17 February 2011, C-52/09, Telia Sonera Sverige).

[31] While Apple allows users to consume content such as music, e-books and audiobooks purchased elsewhere (e.g. on the app developer's website) also in the app, its rules prevent developers from informing users about such purchase options, which are usually cheaper.

[32] Although this is without prejudice to the possibility of limiting such uninstallation in relation to software applications that are essential for the operation of the operating system or device and cannot technically be offered by third parties on a stand-alone basis.

[33] In any event, the gatekeeper shall not be prevented from taking proportionate measures to ensure that third party software applications or software application stores do not jeopardise the integrity of the hardware or operating system it supplies.

[34] According to that doctrine, a refusal to supply is unlawful under Article 102 only if (i) the good or service in question is indispensable for the production of another good or service, (ii) it constitutes an obstacle to the emergence of a new product for which there is potential consumer demand, (iii) it is not objectively justified, and (iv) it is likely to exclude all competition on the derived market. See, in particular, judgments of 26 November 1998, Oscar Bronner GmbH & Co., C-7/97, ECR I-7791 and of 29 April 2004, IMS Health GmbH & Co. OHG C-418/01, ECR I-5039.